Who killed Lucy Beale? Will Joe Miller go down for Danny Latimer’s death? The nations is gripped by crime, murder and court room drama. Well, you may not have a clue what I am talking about if you don’t watch EastEnders or Broadchurch. But if I mention Jack the Ripper or Dr Crippen then these at least are names that will be familiar. Murder has fascinated us through the centuries, whether it is fact or fiction. Notoriously brutal crime stories often seem to be handed down like folk tales, each generation looks with modern eyes on horrific acts that are never dimmed by the passage of time. Often the only thing that changes is our understanding of the evidence, how quickly forensic methods move on, where once a DNA sample would have been an unimagined weapon in the policeman’s methodology, a whole new armoury is opened up with technical medical advances.

Who killed Lucy Beale? Will Joe Miller go down for Danny Latimer’s death? The nations is gripped by crime, murder and court room drama. Well, you may not have a clue what I am talking about if you don’t watch EastEnders or Broadchurch. But if I mention Jack the Ripper or Dr Crippen then these at least are names that will be familiar. Murder has fascinated us through the centuries, whether it is fact or fiction. Notoriously brutal crime stories often seem to be handed down like folk tales, each generation looks with modern eyes on horrific acts that are never dimmed by the passage of time. Often the only thing that changes is our understanding of the evidence, how quickly forensic methods move on, where once a DNA sample would have been an unimagined weapon in the policeman’s methodology, a whole new armoury is opened up with technical medical advances.

The Wellcome Collection have taken this theme for their new exhibition – Forensics – the Anatomy of Crime. The gallery housing it is the last public space to open in their £17.5 million transformation as a destination for the ‘incurably curious’. The Wellcome Trust’s collections are uniquely placed to serve as a meeting point of medicine, life and art. Forensics typifies that exploration and walks us hand in hand into the moments and aftermath of death.

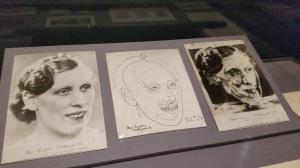

I can’t deny some parts of this exhibition are rather grim and shocking; Alphonse Bertillon’s early crime scene, ‘God’s Eye’ photos from the 1880s, brutal murders coldly displayed in black and white; autopsy stitching and cross sections of brain are not for the faint hearted. But whilst some artefacts may be a struggle, they play a part in our understanding of the forensic process and ultimately our fascination with death. They are the backdrop to the early groundbreaking scientific techniques such as the Marsh Test for the presence of arsenic, first published in 1836 and used to convict the murderer of Marie Lafarge in 1840, and the facial reconstruction method used by John Glaister Jr and James Couper Brash to identify Isabella Ruxton in 1935.

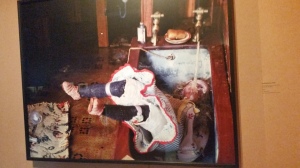

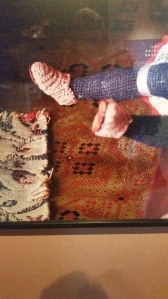

The exhibition takes you methodically through the forensic process in 5 steps, from Crime Scene, Morgue, Laboratory, Search and finally Courtroom. I think I was lulled into a false sense of the nature of the displays, when the first section I came to was the Nutshell Dollshouses created by Frances Glessner Lee in the 1940s. They are weirdly comic and yet disturbing miniature depictions of crime scenes, used not to solve the crime but in order to note the direct and indirect evidence. It is hard to see inside the tiny rooms, but Corinne May Boltz’s more recent photographs really bring out the detail. Immediately I look at crocheted slippers, with sensible grippy soles and I am convinced she didn’t slip into the bath…..

I certainly never played with my Barbie doll’s house in this way, framing Ken with a Ribena juice blood splatter or two up the walls. I couldn’t help but laugh at the film clip of the Baltimore Police and Chief Medical Officer debating the miniature evidence. If you have ever seen the ‘Wire’ you will know why it all seems faintly ridiculous, I couldn’t imagine Jimmy McNulty patting down Barbie’s erstwhile companion Ken for a ‘G Pack’.

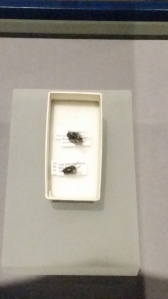

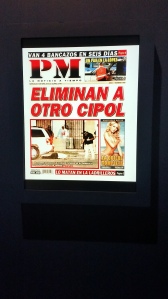

But as I move from dollshouses to maggots and blow flies, used to forensically date the time of death, removed from a 1935 Buck Ruxton murder victim, you realise that this is all rather serious. I am amazed this type of evidence was used as early as 1935, I can’t imagine how hard it must have been to use this type of information to convince a jury in those early days. Then I glance up and see art work by Teresa Margolles, front pages of a Mexican newspaper showing brutal drug murders, strangely glamourised with busty blondes in the worst form of tabloid excess. I kind of lose my way a little at this point in shock.

There are a lot of hard-hitting exhibits, I certainly recommend a swift journey through ‘The Morgue’. But I can’t deny it is fascinating. What you sense is the drive to not only find a killer and cause of death, but a reason behind such brutal actions. This is where forensics so often leave a blank, inside the mind of a killer.

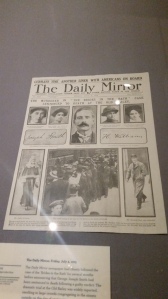

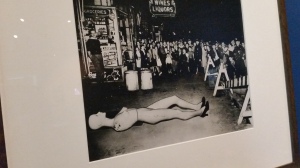

It feels so modern, our obsession with crime – tv dramas flood our screens, crime authors are ever popular, but when you see the front pages reporting the Jack the Ripper Case, the detailed sketches and court photographs of Dr Crippen and his lover, you quickly get the sense that we have always had the need to understand shocking acts of violence and find out ‘whodunit’. This sensationalism is nothing new, perhaps we just use different formats to get our ‘murder fix’. In particular the surreal crime scene photo from New York in 1944 comes to mind, a mannequin replaces the recently removed body, the crowds, children in front, all stand around and stare, spectres at the feast.

Before becoming overwhelmed with grisly detail I take a step back and appreciate the science behind the forensic process. The words speak for themselves ‘morgue’ from the French ‘to peer’, ‘autopsy’ the Greek translation ‘ to see with one’s own eyes’. You realise this attempt to question the dead goes back to the 13th century, there is incredibly detail in the 196os notebooks of pathologist Keith Simpson. There is skill and time and intent involved, to find the answers from those who can no longer speak.

The section I most enjoyed was ‘The Laboratory’, learning about the origins of fingerprinting and the ultimate celebrity selfie, the mugshot, was fascinating. I thoroughly enjoyed the 1934 British Pathe film ‘The Fatal Fingerprint’ with its rather bonkers moral of -“Never let your fingers know what you are up to”.

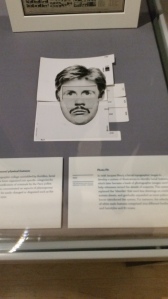

The 1970s photo fit, so often spoofed, with a mind-blowing 204 foreheads and 89 noses, is the ultimate game of Mr Pop. But joking to one side, the insightful video by forensic scientist Angela Gallop sets a lot of the evidence gathering methods into their place, they are nothing without context and interpretation. We can all recall cases that have dramatically collapsed with human error on collection of evidence or the presumption of guilt on forensics that have later been prone to doubt due to cross contamination.

It is with a certain irony that the final section focuses on Dr Crippen, who was convicted partly on the forensic evidence presented by the British pathologist, Bernard Spilsbury, who worked a number of famous cases. A body in the basement, presumed to be Dr Crippen’s wife because of scar tissue that linked to an operation Cora Crippen had on her abdomen. More recent DNA testing on the sample now places doubt on that claim, as the sample is more likely to be from a man than a woman. Suddenly even the forensic infallibility can seem a fragile thing. I wonder in years to come how accurate DNA testing will appear to us with even more advances in scientific techniques.

As I finally push my way through the frosted doors, I have been given a tremendous amount to think about, and I have learnt a huge amount too. At the heart of every section of Forensics, an Anatomy of Crime, is our fascination with murder and death. It is the work of anatomists, forensic scientists and crime scene technicians that feeds that fascination. The Wellcome Collection has given the visitor a real opportunity to step away from television screens, from fantasy and drama, and step into the very real world of forensics. It is perhaps not an easy journey, but curiosity is an unquenchable human trait and it is one that the Wellcome Collection attempts to satisfy with every new exhibition.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Forensics: the anatomy of crime is a free exhibition opening on Feb 26 February 2015 – 21 June 2015 at the Wellcome Collection

Terrific review. The mugshot – the ultimate celebrity selfie – so true!